There is always a beginning. I reflect my ancestry and hope to do it justice by continuing to survive creatively. The complexity of our post-modern lives has both limited and made limitless our capabilities to reference our past. While many of us are blessed with mobility and migration, we are similarly plagued with displacement, political corruption and social status-quos. We flock to museums and gawk over our inherited histories, spiritually disconnected from the artifacts of the deceased. We consume official narratives at every angle, whether it be through our history textbooks, television sets, radios, computer or mobile screens. But we rarely take the time to heal and tell our own story. It is through artwork and teaching that I strive to empower our own stories, for those whose voice is nowhere to be heard in the mainstream, or to simply question the official narrative and its intentions. When I reference Sumerian mythology through my research and artwork, it is not only a nod to my roots, but rather an attempt to discover the links that bind our time with theirs. We are not so different after all, except that what was once analog is now digital, give or take the 7,000 years that span in between. But the underlying statement in my work is that I’m rewriting my own history, and remembering some of the spiritual tools that we lost somewhere along the way.

History repeats itself after all.

[Inanna "The Queen of the Night" (Southern Iraq, c. 1765-1745 BC). British Museum Department of the Middle East. Image courtesy of the author.]

[Inanna "The Queen of the Night" (Southern Iraq, c. 1765-1745 BC). British Museum Department of the Middle East. Image courtesy of the author.]

The mythology of Inanna, the Sumerian Goddess of war and fertility, has been a repetitive symbol in my studies and references. In my attempts to find the commonalities between this ancient deity and our modern day struggles, I have found Inanna everywhere. Last week, I scrambled my way to the British Museum only hours before leaving London on a short trip to look for Inanna. I found her there, perhaps smaller and less significant than I had imagined her, set in clay, ancient yet surviving. I felt strange bearing witness to the traces of my past, particularly in the context of a museum that is complicit in acquiring such a large fragment of our shared history through colonization. At the same time, I acknowledge the looting, neglect and black market trading of the artifacts that remained in Iraq. Eavesdropping on the museum guide, and reading the little placards, I questioned how our history was assumed, written and approved.

Observing the artifacts, it was frustrating realizing that we are continuing a tradition of inherited violence. I was sad that our obsession with battles has not wavered, and our addiction to building has only increased.

In the process of reflecting a re-imagined and subversive reality through my work, the ugly face of exploitation, corruption, violence and suffering infiltrate my space. It is everywhere, no matter how hard our governments or institutions try to hide it. Moreover, the same museums that give us insight to our histories hide countless other truths in their storage rooms, deeming them historically insignificant or otherwise too significant. It is omission that is most dangerous when it comes to our abilities to self-reflect as a people. It is in the face of adversity that we need to be the most aware of our ancestors’ triumphs and weaknesses, and the tools we were innately given to overcome it. However, in today’s big brother-esque information era, we are limited in our overwhelming freedom.

The only way I have learnt how to overcome the limitations of history is by reclaiming the images that are supposedly meant to represent us but in fact hold us down instead. Experiencing the gross misrepresentation of Iraqis, Arabs and Muslims in Western media post-911, and particularly during the illegal invasion of Iraq, I collected many megabytes of media images that represented my people as one-dimensionally oppressed or violent. I used the process of reclaiming those images through subversive collage for many years, most intensely during the production of the Warchestra series, a multimedia painting and sound installation. Conceptually, the Warchestra project was rooted in intense identity politics that blended my own position as an Iraqi-Canadian spectator to the political dynamics of the ongoing war in Iraq.

[Sundus Abdul Hadi, "Ministry of Justice (Conductor)" (2010), from the Warchestra series. For accompanying audio from the installation of the series click here. Image copyright the artist.]

[Sundus Abdul Hadi, "Ministry of Justice (Conductor)" (2010), from the Warchestra series. For accompanying audio from the installation of the series click here. Image copyright the artist.]

By meditating on images of violence and suffering and creating a re-imagined, reinvented landscape of war, I neglected the negative impact that the work was doing to my spirit. Upon completion of the Warchestra series in 2010, I realized that the precious creative energy that we manifest can be so fragile. My sensitivities were heightened due to the personal connection I had to the subject matter (Iraq), and the shifting relationship I had with it as both a spectator and participant. I had to reassess my process.

-

To put things in perspective, my beginning started from my artist mother and architect father, from whom I learnt the importance of creative expression and the significance of my Iraqi* roots. [*In an attempt not to make this writing too identity-centric, I encourage whoever is reading to replace my country of origin with their own, as we all have a shared history and a common experience.]

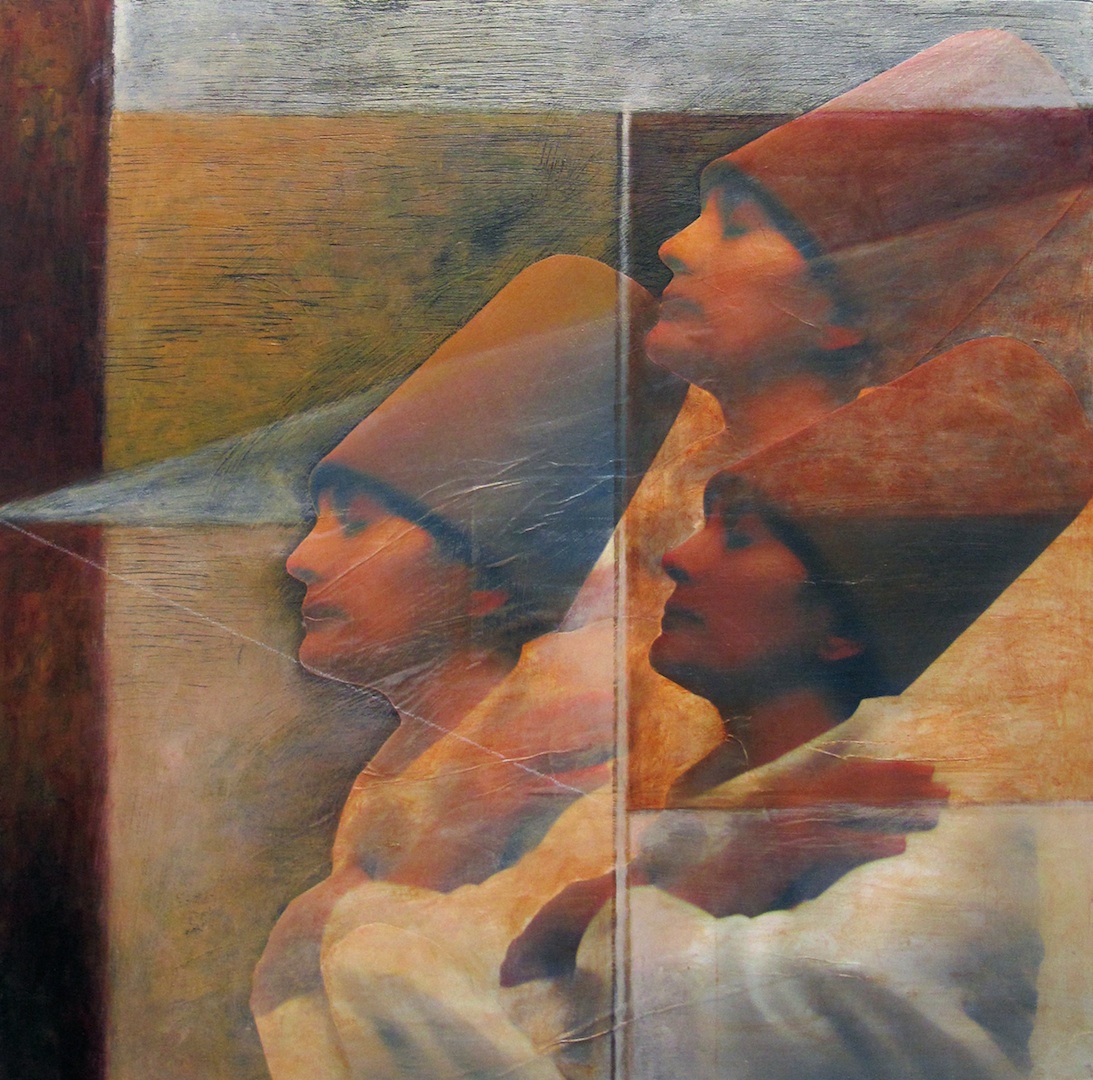

I learnt from my mother Sawsan Alsarafs’ urge to create and make sense of her experiences through images. As I became an adult, our artistic paths converged and diverged. Through her Sufi Path series, I saw her attempting to tap into the space of healing and spirituality that I had neglected for so many years. Her images embody illumination, not only on an aesthetic level with her deliberate use of light, but through the unguarded yet poised use of her own image in a traditionally male role as a dervish. Her use of repetition is ritualistic, and reflects the internal process of art-making in a positive pattern.

[Sawsan Alsaraf, "Divine Light" (2012), from the Sufi Path series. Image coypright the artist. Courtesy of the author.]

[Sawsan Alsaraf, "Divine Light" (2012), from the Sufi Path series. Image coypright the artist. Courtesy of the author.]

Watching her process encouraged me to tap into my own spiritual path as a reference point in my artwork, while striving to strike a balance between the social issues that drive my work and my own ethereal needs as an artist and woman.

To go back to Inanna, her journey represents both ascent and descent. She descended to the underworld and also ascended back to the heavens. What a reflection of our lives, and the struggles that we endure. To me, her story represents darkness, transformation, flight and light. With my transition from Warchestra into the Flight series, I experienced a lightness of being that would have only been possible after emerging from darkness. Post-Warchestra, I embarked on a cathartic project that is based on the concept of human flight and uprising and was initiated in 2010 during a two-week residency in the West Bank, Palestine. Through this project I explore digital collage and collaboration, as I worked with images by my sister Tamara, who is also an artist.

[Tamara Abdul Hadi, from the Flying Boy series. Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of the author.]

[Tamara Abdul Hadi, from the Flying Boy series. Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of the author.]

Tamara Abdul Hadi’s photographs, especially those of young boys from Beirut and Akka jumping into the Mediterranean, inspired me greatly. I immediately imagined these youths outside of their context, in flight, yet simultaneously reflecting the struggles that live in their surroundings. As I explored the concept of flight, the pivotal “Arab Spring” revolutions sparked around me, and the project was further nurtured by the escalating changes in the region. I went back to a place of youthful imagination, trying to reinterpret life’s struggles through the eyes of a child, simplifying the message enough for a child to understand and relate to, as in “Rumanna”.

[Sundus Abdul Hadi in collaboration with Tamara Abdul Hadi, "Rumanna" (2011). Image copyright the artists.]

[Sundus Abdul Hadi in collaboration with Tamara Abdul Hadi, "Rumanna" (2011). Image copyright the artists.]

Recently, my artistic projects are centered on the fragility and resilience of the human condition in abnormal circumstances of war, occupation and survival. Our civilization is so young in comparison to the heritage that precedes us. There is much to learn from those that came before us. Many years ago, at the start of my artistic journey, my father passed me a book about the Sufi tradition in Islamic architecture. The book holds countless truths about the symbolic, spiritual and cosmic connections between colour, matter, shape, and space. It is also a clue towards the importance of intention when creating an artwork, and how it is perceived. If the physical world is a symbol and image of the spiritual world, artists have a great responsibility to reflect a narrative that both depicts and interprets the condition of our time. The Baghdad Modern Art School’s manifesto said it in 1951, and it couldn’t ring more true today, that an artist has “a duty to interpret society by depicting current events and recording the social conditions of the country.”

In my quest to find the balance between the social and the spiritual, the past and the present, and the positive and the negative, my references are many and diverse. As much as 1,500 words can describe my process, there is no better medium to truly grasp it than through the images I reference and the ones I create. If history really does repeat itself, wouldn’t we want to offer an alternative?

[The above post is part of Visuals in 1500, a new Jadaliyya Culture series on aesthetics.]